Soms ben je zo trots op een essay dat het pijn doet hem ergens in een lade te laten verstoffen of hem achter te laten in een nooit meer geopende map op je computer. Om voor deze essays toch een plekje te vinden, hebben we Essay Uitgelicht, waar we ze vereeuwigen op deze site! Deze keer: Contemporary Film Music Production that Changed the Hollywood Score, geschreven door Manuel Gutierrez Rojas in het kader van het mastervak Music and the Moving Image.

Heb je zelf een essay geschreven dat je wil laten zien aan de wereld? Stuur hem op naar siteco@hucbald.nl!

[Danny] Elfman approached Batman with credentials that seemed less than ideal. [Tim] Burton wanted a full-blown orchestral soundtrack, not the electronic reduxes dished out by many of today’s young homebrew Hollywood composers. Though self-taught, with none of the conservatory schooling that enables Jerry Goldsmith or John Williams to score for entire divisions of symphonic musicians, Elfman took the gig, cranked up his Mac II, called orchestrator Steve Bartek [. . .] and eventually came up with what may qualify as the blockbuster soundtrack of the year.[1]

This critical observation of Robert L. Doerschuk in 1989 about Danny Elfman’s now acclaimed Batman (dir. Tim Burton, 1989) score assumes that Elfman did not have the required skills to write a proper orchestral soundtrack, but relied on computer software and an orchestrator to accomplish his task. While this assumption about relying on the orchestrator is strongly refuted by Steve Bartek himself when it comes to how Elfman composes,[2] Doerschuk’s statement does not seem far off to how film music is produced for the last two decades. Junkie XL’s Mad Max: Fury Road (dir. George Miller, 2015) and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (dir. Zack Snyder, co-composed with Hans Zimmer, 2016) seem to be today’s expected blockbuster Hollywood score: rich in percussion and strongly layered with strings, but relatively lacking any leitmotiv or strong melodic content. Furthermore, Hans Zimmer’s scores and those of his Remote Control Productions team differ little from formula and style in whatever type of recent film, be it an action swashbuckler film such as Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (dir. Gore Verbinski, comp. Klaus Badelt, 2003) or a historical epic such as Gladiator (dir. Ridley Scott, co-composed with Lisa Gerrard, 2000).

This paper will examine to what extent Doerschuk’s notion of film composers using computer software rather than relying on skills or formal training has become reality. Possible reasons for embracing digital technology are: (1) the very tight scheduling of the film music for motion picture productions, (2) the ease of composing and finalising a scoring product with virtual instruments during the production phase, and (3) the apparent musical direction of style towards sound and rhythm rather than melody and counterpoint. I will use several books, articles, a private interview with film composer Maxim Shalygin, music software, and videos for supporting my paper.

Film Music Scheduling

The time schedule wherein film composers can do their job is usually very tight, as Emilio Audissino points out: “[I]n the classical studio system, composers were generally required to write a score in eight to ten weeks; these days, two-hour-long scores can be commissioned within a three- to four-week deadline.”[3] Some extreme examples of tight schedules are the film scores for the remake of King Kong (dir. Peter Jackson, comp. Howard Shore, 2005) and the epic Troy (dir. Wolfgang Peterson, comp. James Horner, 2004). For Troy James Horner had to rescore the whole film in just ten days after the initial score of Gabriel Yared, which took him a year to complete, was rejected and abandoned due to a disappointing test screening of the film.[4] For King Kong, Peter Jackson and Howard Shore broke their strong collaboration due to unknown circumstances and James Newton Howard had to complete a new score for a three-hour film within five weeks.[5] Christian Clemmensen describes this eleventh-hour operation of scoring King Kong:

[T]he process required a significant employment of internet technologies to realize. Jackson and Howard would sometimes both view feeds of the recording sessions remotely (with Howard composing while the score was being recorded across town), and all three locations would be linked for communication purposes. Amazingly, the composer and director would not meet in person until the highly touted debut of the film.[6]

Do take into consideration that this internet-relying project took place in 2005. Now, mock-ups of orchestral pieces are often a way for a composer and his or her director/producer(s) to efficiently and cost-effectively interact with each other. Indeed, composing music without the help of a computer takes significantly more time. John Williams admits his digital illiteracy and as a consequence for his slow process of composing film music compared to young digital literate film composers: “I am slow, I don’t have a computer. I only have paper and pencil. So, I write every note. Therefore, I can’t quite keep the schedules like my younger colleagues would be able to do who use synthesizers.”[7] Interestingly, according to Hans Zimmer, the constantly improving technology will adversely affect music production. He says:

I started making music with computers in the late seventies [. . .] when you had to go and actually write in code and stuff like this and when you write on paper you’re basically writing an instruction manual for other people to perform. When you’re writing in the computer, or the way I do, is you perform every note. At one point or the other, every note that is in the score has been played by me and being fiddled around with by me, so it takes a lot longer. Technology doesn’t make things faster, it makes it slower if anything, because it opens up endless possibilities—plus you have to learn how to deal with it so it doesn’t drive you.[8]

Nevertheless, while technology might not have made things faster, it certainly has changed the process of composing for film.

Digital Film Music Production

The short documentary “The Marvel Symphonic Universe” discusses the problem of “temp music” alongside “modern nonlinear editing” as a reason for lack of creative and memorable film music over the last twenty years.[9] Temp music is a draft track of pre-existing music by the production of a film, usually the director, to give the film composer an idea of what kind of style, mood, and tension he or she should compose for a given cut of the film. The documentary discusses the following problem:

Before temp music became popular, directors would often reference other music as a way to talk to the composer. But what changed everything was modern nonlinear editing which allowed a director to put their favourite music in the movie and have the editor cut to it. [. . .] Now, the director points to the temp and says: “Make it like that.” And it’s not because the music is the right choice, but because they’ve listened to it.[10]

At this years BUMA Classical Convention, a Dutch conference for professionals working in the classical music industry, I talked to film composer Maxim Shalygin about the current situation of film production and how a film composer’s creative power appears to have been diminished and handed over to the director and the producer. He responded:

Current film composers just combine samples which are already arranged—huge libraries from samples. They take samples from a recorded real orchestra and combine it together with a piano melody on top and that’s it! There are really just a few people like Jean-Luc Godard who still do crazy stuff that is really good. Believe me, you cannot imagine how many samples are ready. With a push of a button you can transpose samples so a collection of different samples can fit together. You can make a piece in half an hour if you want to make it a standard.[11]

Virtual Studio Technology (VST) libraries[12] and pre-arranged music libraries fit Shalygin’s concern. For instance, EastWest is a company that creates VST libraries of the Stormdrum series which consists of preprogrammed percussion samples, while 8Dio’s CAGE Strings is a collection of preperformed atonal and avant-gardist orchestral effects.[13] Film composers do not have to hire orchestras or recording studios. In some instances it is not even necessary to be skilled in compositional techniques: with CAGE Strings software one can construct atonal pieces without the need to understand how to write them at all. Just by cutting and pasting the software’s prerecorded atonal performances, the atonal track will be created.

In addition, although at this time VST libraries have come a long way with their flexibility, it is still very hard to create convincing real-sounding pieces if a more melodic and contrapuntal approach is required. Very minute characteristics of real performances can still only be artificially suggested. Musicians’ expressions will increase the more melodic the material gets. Therefore, if film composers have to rely on VST libraries for the film production, compromises have to be made compositionally to hide the artificiality that are VST libraries. This phenomenon of an artificial performance that, though incredibly convincing, is not there yet by a small margin, can be connected to Masahiro Mori’s “uncanny valley.”[14] The “uncanny valley” is a concept wherein a robot gets more realistic the more human it looks, but “uncanny” at the point of it being almost human (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Affinity towards a robot exponentially increases up until it becomes almost human when suddenly the robot becomes eerie and “uncanny.” Reprinted from “The Uncanny Valley,” IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine.

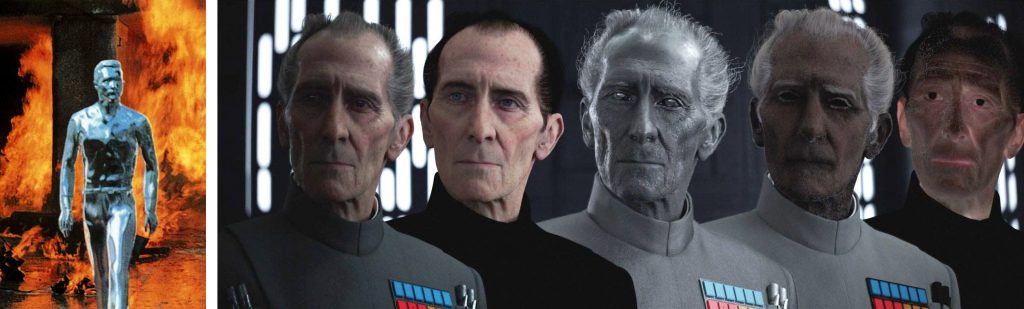

The concept has been linked to computer-generated imagery (Figure 2) which if used sparingly, can be very convincing, such as in creating a human cyborg of liquid metal in Terminator 2: Judgment Day (dir. James Cameron, 1991), but eerie in the attempt to completely digitally recreate human beings, such as inserting a computer generated Peter Cushing (1913–1994) in the very recent Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (dir. Gareth Edwards, 2016).

Figure 2. T-1000, the human cyborg in Terminator 2: Judgment Day (left) and Peter Cushing digitally recreated in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (right). Industrial Light & Magic/Lucasfilm

The “uncanny valley” can, however, also be connected to digital music production using VST libraries. Creating convincing basic, sound-based Hans Zimmer–esque music will not be a problem such as Zimmer’s “Chevaliers de Sangreal” from The Da Vinci Code (dir. Ron Howard, 2006) as covered by notapix.[15] However, classical Hollywood–styled John Williams–esque music can easily be considered fake such as Williams’s “Main Title” from Star Wars (dir. George Lucas, 1977) as covered by Le Compositoire.[16]

To mask these artificial artifacts, film composers need to adapt their way of composing. In his dissertation “What Effect has the DAW had on the Composition of Modern Orchestral Film Music?” Alastair A. Adams discusses this problem:

Composers are often forced to use certain instruments over other merely because the sample for the desired instrument is not good enough, or bizarre combinations or sizes of ensemble have to be conglomerated in order to make something sound even remotely realistic. As composer John Graham states: “I never hand over even a demo of a piece unless I think it sounds practically good enough to put into the film even without the live players. If that means that I have, in effect, 200 strings or 18 French Horns playing in a passage, I care not.”[17]

Another problem is inputting digital instructions—using MIDI technology[18]—into a digital audio workstation or DAW. Contemporary film composers often use a digital keyboard for this purpose. For instance, inserting a virtuous violin track using a keyboard requires great skill from the player to imitate.[19] Film composer Stuart Kollmorgen comments that: “For me the biggest danger working in my DAW is falling into the trap of only writing things I can play in real time. I should have slowed it down to a tempo at which I could play with feeling.”[20] Composers could even perform music in a DAW with an instrument in mind which in real life could not be performed that way. For instance, in Vangelis’s “Hispanola [sic],”[21] the title track of 1492: Conquest of Paradise (dir. Ridley Scott, 1992), one can hear a mixture of the English Chamber Choir and singer Guy Protheroe with synthesised instruments performed by Vangelis. The prominent flamenco guitar in this track in D phrygian is clearly not real: the bends at the beginning (time cue 0:04–0:12) are too smooth and especially for a flamenco guitar impractical and everytime the guitar sound plays along with the ♭II chord (time cue 0:31), the notes are played together as one would play on a keyboard; a guitarist would play the notes closely next to each other, but not at the same time.

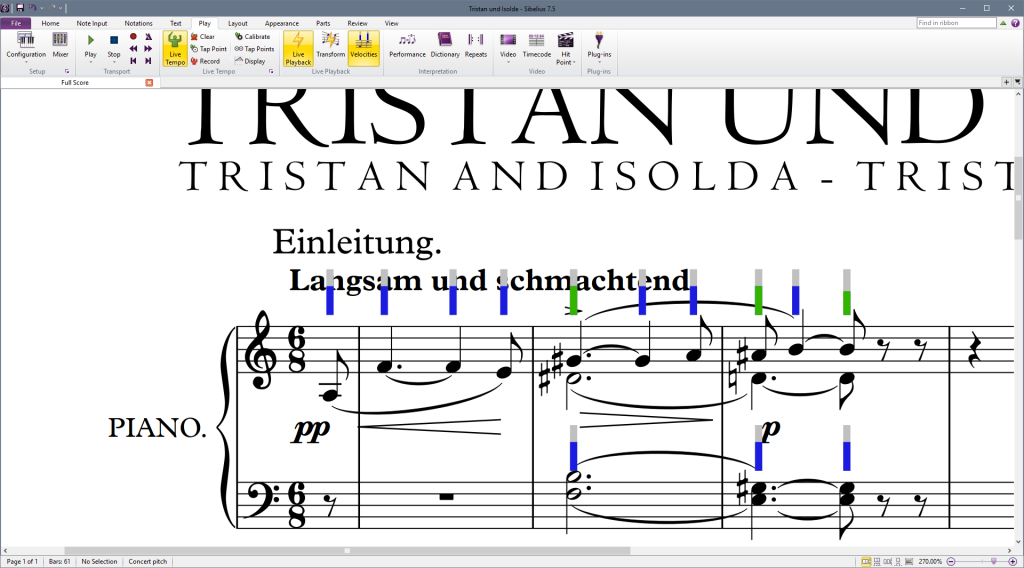

Another option for inputting MIDI information is the use of music notation software that supports VST technology such as Sibelius.[22] For instance, in Sibelius, one could notate music, and the program then can translate it into MIDI so that VST libraries can be triggered and “perform” the music notation as audible music. However, human elements of dynamics and timing will not be transferred because the program does not understand them (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde transcribed in Sibelius. The vertical bars describe the volume of each note. The program clearly ignores the instructions of articulation and expression, simply because it cannot understand it: every note shows the same volume (80 out of 127).[23] The software performs the timing of this part very mechanically as well. Transcribed by the author.

Figure 3. Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde transcribed in Sibelius. The vertical bars describe the volume of each note. The program clearly ignores the instructions of articulation and expression, simply because it cannot understand it: every note shows the same volume (80 out of 127).[23] The software performs the timing of this part very mechanically as well. Transcribed by the author.

Though more recent music notation software have humanising effects included that can make digitally notated music sound less mechanical, they are still approximations. A compromise of human input along with digital music transcription might be the way forward. Steinberg’s very recent Dorico tries to be that software.[24] Only time will tell whether these compromising developments of DAWs and music notation software can improve film composers’ freedom, to not need to confine themselves to the limitations of digital technology in order to sound real and not computer generated.

Departure from the Classical Hollywood Music Style

One final possible reason for the growing use of digital technology is the departure from the classical Hollywood sound. Much of today’s film music is set at the background and functions more as an environmental sound supporting sound effects rather than as a narrator that leitmotivic, thematic, and melodic material could do prior to this development. Emilio Audissino examines this change:

During the classical period, the sound-effect track was the third element of the sound track, less important than dialogue and music, since monaural technology and analogical systems made it infeasible to have many tracks simultaneously in the sound mix. In contemporary cinema, however, the sound effect track holds a prominent position in the sound design. This supremacy is encouraged by the huge potential of digital processing and the many technologies of sound diffusion that can create a surrounding and hyper-realistic aural “super-field” not only in theaters but also in homes theaters. Therefore, music itself has mostly been pushed down to the third, lowest position in the sound track.[25]

This means that film music may musically be very generic and unmelodic, not necessarily to mask the use of samples and digital software, but because it is out of fashion. There is no demand for it—not at this time at least.

Conclusion

Film music production has most definitely changed over the last two decades. The act of composing turned from being an abstract process of music writing which slowly developed into performing rehearsals into recording sessions etc. to an immediate process of instant musical performances of the film composer’s, director’s, and/or producer’s idea, that could be easily tweaked further up to the final result. The demand for more sound-based, environmental music to support the more prominent sound effects, pushed the film score from the motion picture to the background, which in turn dramatically removed the film score from the classical Hollywood film music sound. As a consequence, contemporary film composers do not need to be formally trained or even musically skilled to do their job—especially considering VST libraries exist that have preperformed atonal symphonic recordings (8Dio’s CAGE Strings) and preprogrammed high quality percussion loops (EastWest’s Stormdrum). A thorough understanding of digital music technology and computer technology in general is however recommended. Whether this process will change, whether a return of the classical Hollywood music style can be expected, I cannot say. Robert L. Doerschuk may had it at the wrong end with Danny Elfman, but he most definitely had it at the right end with many other composers several decades later.

Bibliography

Adams, Alastair A. “What Effect has the DAW had on the Composition of Modern Orchestral Film Music?” Diss. University of Central Lancashire. Academia. Accessed December 20 2016. www.academia.edu/12232755.

Audissino, Emilio. John Williams’s Film Music: Jaws, Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and the Return of the Classical Hollywood Music Style. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2014.

Clemmensen, Christian. “Editorial Reviews: King Kong.” Filmtracks. Accessed January 17 2017, www.filmtracks.com/titles/king_kong05.html.

———. “Editorial Reviews: Troy.” Filmtracks. Accessed January 17 2017, www.filmtracks.com/titles/troy.html.

Coleman, Michael. “The Sound and Music of The Dark Knight Rises.” SoundWorks Collection. Santa Monica: Remote Control Productions, 2012. Vimeo video clip. Accessed January 18 2017. vimeo.com/46759301.

Doerschuk, Robert L. “Danny Elfman: The Agony and the Ecstasy of Scoring Batman.” Keyboard, October 1989, 83–95.

Halfyard, Janet K. Danny Elfman’s Batman: A Film Score Guide. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2004.

Kendall, Lukas. “Interview: Steve Bartek.” Film Score Monthly, December 1995, 14–16.

Mori, Masahiro, Karl F. MacDorman, and Norri Kageki. “The Uncanny Valley.” IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 19, no. 2, June 2012.

Nepales, Ruben V. “John Williams Looks Forward to Scoring New ‘Star Wars,’ ‘Indiana Jones.’” Philippine Daily Inquirer. Accessed January 18 2017. entertainment.inquirer.net/121095/

john-williams-looks-forward-to-scoring-new-star-wars-indiana-jones.

Satterwhite, Brian, Taylor Ramos, and Tony Zhou. “The Marvel Symphonic Universe.” YouTube. Accessed January 17 2017, youtu.be/7vfqkvwW2fs.

Shalygin, Maxim. “How to Survive as Composer?” BUMA Classical Convention. Interview with the author at the BUMA Classical Convention, Utrecht, October 13, 2016. Transcribed and translated from Dutch to English by the author.

Motion Pictures

1492: Conquest of Paradise. Directed by Ridley Scott. Produced by Alain Goldman and Ridley Scott. Hollywood: Paramount Pictures, 1992.

Batman. Directed by Tim Burton. Produced by Jon Peters and Peter Guber. Burbank: Warner Bros. Pictures, 1989.

Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Directed by Zack Snyder. Produced by Charles Roven and Deborah Snyder. Burbank: Warner Bros. Pictures, 2016.

The Da Vinci Code. Directed by Ron Howard. Produced by John Calley, Brian Grazer, and Ron Howard. Los Angeles: Columbia Pictures, 2006.

Gladiator. Directed by Ridley Scott. Produced by Douglas Wick, David Franzoni, and Branko Lustig. Universal City: Universal Pictures, 2000.

Mad Max: Fury Road. Directed by George Miller. Produced by Doug Mitchell, George Miller and P. J. Voeten. Burbank: Warner Bros. Pictures, 2015.

King Kong. Directed by Peter Jackson. Produced by Jan Blenkin, Carolynne Cunningham, Fan Walsh, and Peter Jackson. Universal City: Universal Pictures, 2005.

Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl. Directed by Gore Verbinski. Produced by Jerry Bruckheimer. Burbank: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2003.

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. Directed by Gareth Edwards. Produced by Kathleen Kennedy, Allison Sheamur, and Simon Emanuel. Burbank: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2016.

Star Wars. Directed by George Lucas. Produced by Gary Kurtz. Los Angeles: 20th Century Fox, 1977.

Terminator 2: Judgment Day. Directed by James Cameron. Produced by James Cameron. Culver City: TriStar Pictures, 1991.

Troy. Directed by Wolfgang Petersen. Produced by Wolfgang Petersen, Diana Rathbun, and Colin Wilson. Burbank: Warner Bros. Pictures, 2004.

Music

“Chevaliers de Sangreal.” Written by Hans Zimmer. From The Da Vinci Code. Covered by notapix [sic]. Retitled to “còdexe da vinci Chevaliers De Sangreal hans zimmer cover [sic].” Video clip. Posted 16 March 2009. Accessed January 17 2017. YouTube. youtu.be/7dnlGeoP1VQ.

“Hispanola [sic].” Written by Vangelis. From 1492: Conquest of Paradise. New York City: Warner Music, 1992.

“Main Title.” Written and conducted by John Williams. From Star Wars. Covered by Le Compositoire. Retitled to “Mockup Star Wars par Jean-Gabriel.” Video clip. Posted February 27 2016. Accessed January 17 2017. YouTube. youtu.be/5GVNYuah9is.

Music Software and Technology

CAGE Strings VST-AU-AAX – Kontakt Instruments & Samples. 8Dio. Accessed January 18 2017. 8dio.com/instrument/cage-strings-vst-au-aax-kontakt-instruments-samples. VST software.

Dorico. “Dorico: The New Gold Standard in Scoring Software.” Steinberg. Accessed January 18 2017. www.steinberg.net/en/products/dorico/start.html.

MIDI. MIDI Association. Accessed January 18 2017. www.midi.org. Industry standard music technology protocol.

Sibelius. “The Fastest, Smartest, Easiest Way to Write Music: Express Yourself with Sibelius.” Avid. Accessed January 18 2017. www.avid.com/sibelius.

VST. “VST: The Integrative Standard for Virtual Instruments and Effects.” Steinberg. Accessed January 18 2017. www.steinberg.net/en/company/technologies.html.

[1] Robert L. Doerschuk, “Danny Elfman: The Agony and the Ecstasy of Scoring Batman,” Keyboard, October 1989, 84.

[2] Lukas Kendall, “Interview: Steve Bartek,” Film Score Monthly, December 1995, 15.

[3] Emilio Audissino, John Williams’s Film Music: Jaws, Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and the Return of the Classical Hollywood Music Style, (Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2014), 199.

[4] Christian Clemmensen, “Editorial Reviews: Troy,” Filmtracks, accessed January 17 2017, www.filmtracks.com/titles/troy.html.

[5] Ibid., “Editorial Reviews: King Kong,” Filmtracks, accessed January 17 2017, www.filmtracks.com/titles/king_kong05.html.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ruben V. Nepales, “John Williams Looks Forward to Scoring New ‘Star Wars,’ ‘Indiana Jones,’” Philippine Dialy Inquirer, accessed January 18 2017, entertainment.inquirer.net/121095/

john-williams-looks-forward-to-scoring-new-star-wars-indiana-jones.

[8] Michael Coleman, “The Sound and Music of The Dark Knight Rises,” SoundWorks Collection, Santa Monica: Remote Control Productions, 2012, Vimeo video clip, accessed January 18 2017, vimeo.com/46759301.

[9] Brian Satterwhite, Taylor Ramos, and Tony Zhou, “The Marvel Symphonic Universe,” YouTube, accessed January 17 2017, youtu.be/7vfqkvwW2fs.

[10] Satterwhite et al., “The Marvel Symphonic Universe,” time cue 9:42, youtu.be/7vfqkvwW2fs?t=9m42s, transcribed by the author.

[11] Maxim Shalygin, “How to Survive as Composer?” BUMA Classical Convention, interview with the author at the BUMA Classical Convention, Utrecht, October 13, 2016, transcribed and translated from Dutch to English by the author.

[12] Virtual Studio Technology is a virtual instrument software protocol created by Steinberg. Refer to “VST: The Integrative Standard for Virtual Instruments and Effects” for more information: www.steinberg.net/en/company/technologies.html (accessed January 18 2017).

[13] CAGE Strings VST-AU-AAX – Kontakt Instruments & Samples, 8Dio, accessed January 18 2017, 8dio.com/instrument/cage-strings-vst-au-aax-kontakt-instruments-samples.

[14] Masahiro Mori, Karl F. MacDorman, and Norri Kageki, “The Uncanny Valley,” IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 19, no. 2, June 2012.

[15] “Chevaliers de Sangreal,” written by Hans Zimmer, from The Da Vinci Code, covered by notapix [sic], retitled to “còdexe da vinci Chevaliers De Sangreal hans zimmer cover [sic],” video clip, posted 16 March 2009, accessed January 17 2017, YouTube, youtu.be/7dnlGeoP1VQ.

[16] “Main Title,” written and conducted by John Williams, from Star Wars, covered by Le Compositoire, retitled to “Mockup Star Wars par Jean-Gabriel,” video clip, posted February 27 2016, accessed January 17 2017, YouTube, youtu.be/5GVNYuah9is.

[17] Alastair A. Adams, “What Effect has the DAW had on the Composition of Modern Orchestral Film Music?,” diss. University of Central Lancashire, Academia, accessed December 20 2016, www.academia.edu/12232755, 9.

[18] MIDI is a technical standard created in 1983 which connects computer software with MIDI-supported musical instruments. Refer to the MIDI Association, www.midi.org, for more details (accessed January 18 2017).

[19] Adams, “What Effect has the DAW had?,” 11.

[20] Quoted from Adams, “What Effect has the DAW had,” 11.

[21] “Hispanola [sic],” written by Vangelis, from 1492: Conquest of Paradise, New York City: Warner Music, 1992.

[22] Refer to the following hyperlink for more information about Sibelius: www.avid.com/sibelius (accessed January 18 2017).

[23] Technically the vertical bars describe the velocity of each note which would normally be a result of how fast a musical note is triggered on a MIDI instrument and transferred to the volume of the note.

[24] Refer to the following hyperlink for more information about Dorico: www.steinberg.net/en/products/dorico/start.html (accessed January 18 2017).

[25] Audissino, John Williams’s Film Music,” 197–198.